UPDATE 10/29/13: The World Health Organization has reported their laboratory in Tunis isolated the wild polio virus in samples taken from 10 of 22 Syrian cases being investigated.

One of war’s less publicized though wide reaching consequences is its disruption of public health. The primary impacts of war on health are obvious: combatants (and increasingly non-combatants) suffer injuries and death. The secondary and tertiary impacts are somewhat less obvious, and range from mental and emotional trauma such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to damage to or loss of infrastructure such as hospitals or water sanitation systems.

There are myriad ways in which war can influence the spread of infectious disease. As combatants and non-combatants migrate, they may bring pathogens with them, or become exposed to new pathogens. Refugee camps are not known for exemplary hygiene or medical care despite commendable efforts by well-established NGOs like the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and Doctors Without Borders. Loss of health care workers and health care facilities significantly disrupts surveillance, monitoring, and prevention of infectious diseases.

On October 17, the World Health Organization received notice of a cluster of acute flaccid paralysis in the Deir Al Zour province of Syria. The WHO suspects two of these cases will test positive for polio – health officials wait for laboratory results.

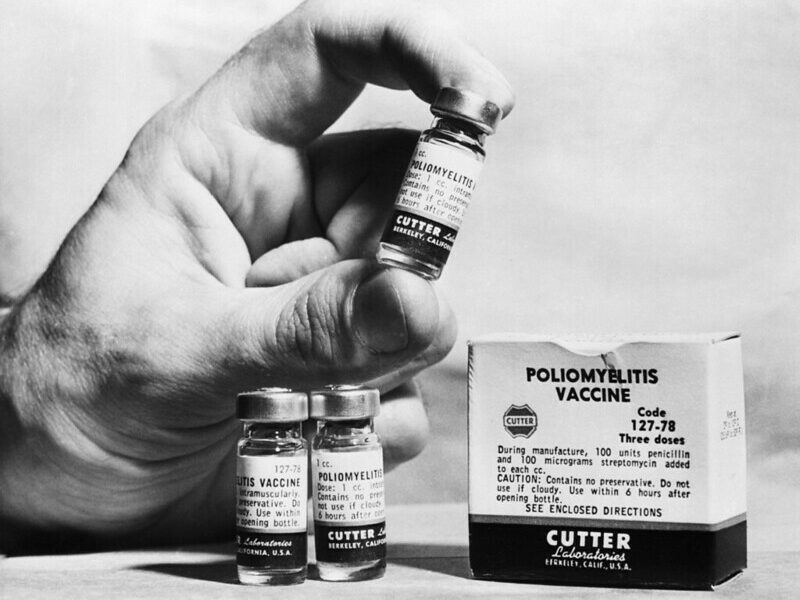

Just a few days later, October 24 2013, we celebrated World Polio Day – a global effort to commemorate the birth of Jonas Salk, who created the first polio vaccine, and to increase awareness of the disease and the effort to eradicate it. In 2012, 223 polio cases were reported. According to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative website, 301 cases have been reported thus far in 2013.

Syria implemented mandatory routine immunization against polio in 1964 and eliminated polio in 1999. This is no small feat. Through email communications, Ananda Bandyopadhyay, a former Surveillance Medical Officer with India’s National Polio Surveillance Project shares his experiences to help us better understand the challenges faced in polio vaccination campaigns. India was long regarded as the most difficult place to eliminate polio and has now gone nearly three years without identifying a case.

In his experience, “each team of vaccinators (2-4 persons in each team) has an assigned geographic area to cover on a day.” A vaccinator, according to Bandyopadhyay, can be a local volunteer, a health official, state/local government official, or staff from the non-health sector. Bandyopadhyay explains that vaccinators may visit between 20 and 80 households in one day – “The number of target households varies by geographic terrain, population density and other variables.” Once at the households, the teams must perform interviews, vaccinate children, and keep documentation of responses and vaccinations.

The WHO identifies different strategies within its six-year strategic plan to eradicate polio, among them: routine immunization, supplementary immunization activities, and mop-up campaigns. Countries that routinely immunize against polio should be able to prevent a resurgence of the disease in the event of an imported case. Supplementary immunization activities include National Immunization Days, during which the goal is to ensure that every child under five is immunized against polio at the same time. If every child is immunized, the virus cannot survive, even if some of the vaccinated do not achieve full immunity. The logistical challenge of immunizing every single under-five child in a given country is clear, so there are also mop-up campaigns, during which vaccinators travel to each household to ensure children are protected against polio. These campaigns often occur in high-risk areas with high population density, poor sanitation and poor immunization rates.

But then there are also mobile populations. Bandyopadhyay explains that in India special “transit teams” were created to ensure that nomadic populations, or those at intersections, public transportation stops or border areas were not left out. The logistical genius it takes to coordinate such a campaign is astounding.

According to Bandyopadhyay, who has also worked on measles outbreak investigations and campaigns, polio presents unique challenges. Because of the household level approach and the enormity of the polio eradication campaign, it “is arguably the most "visible" health program that the global health community has ever coordinated” and this visibility stirs up anti-vaccination sentiments. The security of vaccinators has garnered significant concern recently. Earlier this year, several polio vaccinators were killed in Nigeria and Pakistan. Further, the scale of the campaign comes with enormous economic costs. The costs cover not simply the vaccines but also the necessary human resources at a multitude of levels (administering vaccines, conducting surveillance, responding to outbreaks, coordinating these responses and immunization campaigns).

These challenges exist during times of relative peace. Since spring 2011, Syria has faced civil war and the devastating public health consequences that accompany it. Bandyopadhyay reminds us: “The key is to ensure improved levels of childhood vaccination with better routine (and supplementary, if applicable) immunization activities everywhere, as a continuous process.” [emphasis added]

Ananda Bandyopadhyay closes his email with some wise words:

"In my personal opinion, one admittedly “noble” feature of poliovirus is that it does not have any bias towards caste, creed and religion.. Immunity against the virus, or the lack thereof, is all that matters for the poliovirus. Thus, we as a human race are probably fighting an unequal battle against polio, because we are still divided, based on our religious, political and at times geographical baggage that we continue to inherit, nurture and at times, spread. With the astounding success achieved over the years in cornering the virus to a small geographic foci, hopefully we will all be more united as a global community in the coming days to kick polio out of this planet, once and for all.”

To read more about Ananda Bandyopadhyay’s experiences and work, read his post for the Impatient Optimist, blog of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Bandyopadhyay is currently a Program Officer for the polio program at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. For more on polio, check out past Disease Daily articles, the CDC or the WHO. To track HealthMap alerts on polio, visit healthmap.org/polio.